Man, let me tell you, I never thought I’d spend a solid week of my life researching something as simple as a soccer ball. I mean, it’s just a round thing, right? Wrong. Absolutely wrong. This whole thing kicked off because I was arguing with my neighbor, Steve, about the quality of old football games versus new ones.

Steve, bless his heart, is convinced that every ball made after 1998 is rubbish, claiming the old leather ones from the 70s had “soul” and “predictable flight.” I told him that was utter nonsense—those old balls soaked up water like sponges and weighed 10 pounds by the end of the first half. He scoffed, said I was making it up, and bet me a decent steak dinner that I couldn’t list every official World Cup ball from the 70s onward and explain the actual engineering changes. I had to take that bet. I just had to shut him up.

The Great Database Scramble: Finding the Start Line

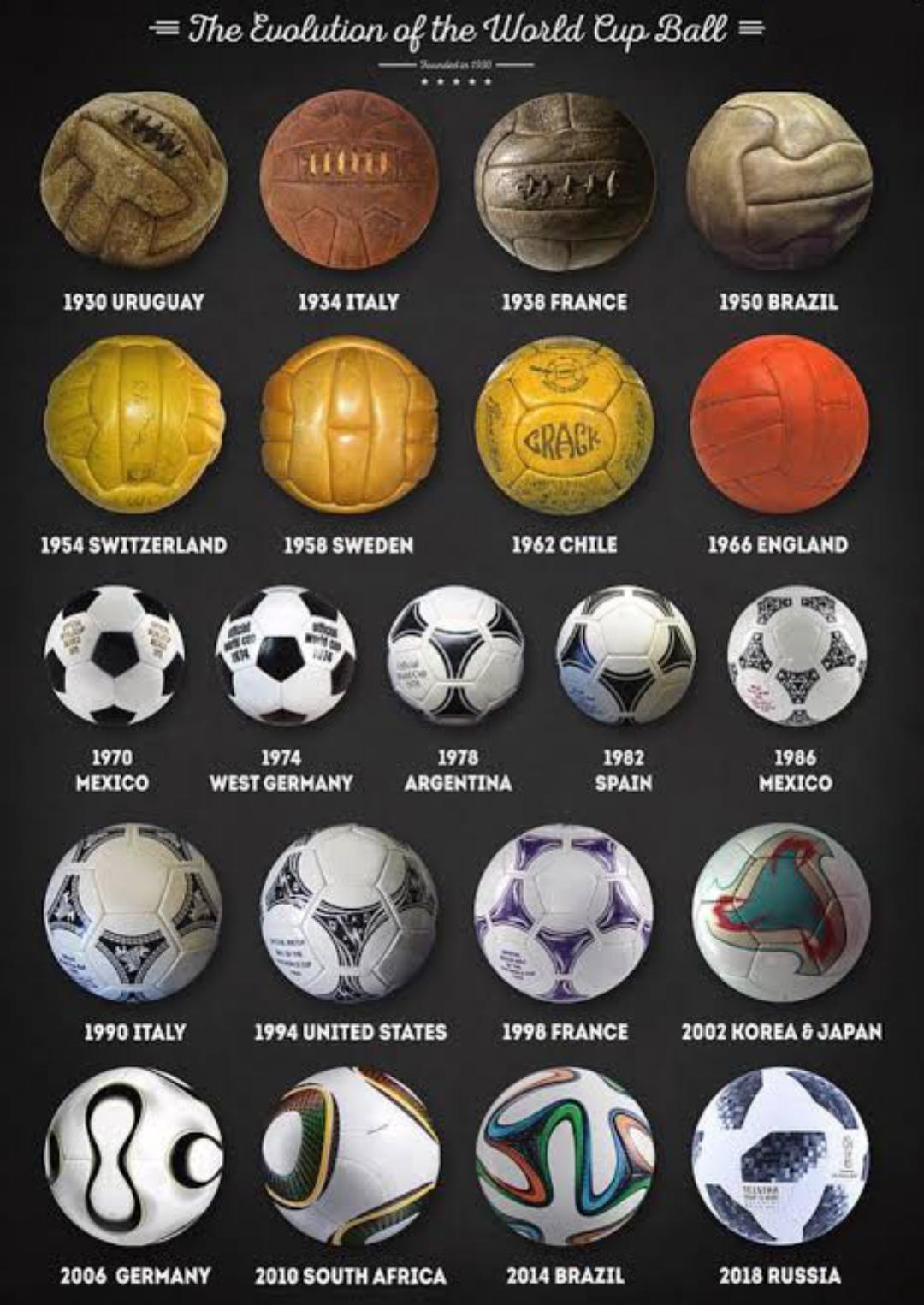

I started the search figuring it would take maybe two hours. I hit the web hard, typing in every variation of “official world cup footballs.” The first problem I ran into was consistency. Some sites started with 1930, listing things that looked more like medicine balls than actual footballs. Others had conflicting names for the balls in the 80s. It was a giant mess. I quickly realized that if I wanted a clear, verifiable technological history, I needed to establish a strict starting point.

That starting point had to be 1970. Why 1970? Because that was the year adidas officially took over and standardized the design. That’s when the balls started getting unique, official names and consistent branding. Before that, it was just “the leather ball used that year.” Useless for a technical deep dive. So, I threw out everything pre-1970 and focused strictly on the adidas era, starting in Mexico.

Verifying the Panels and the Coating

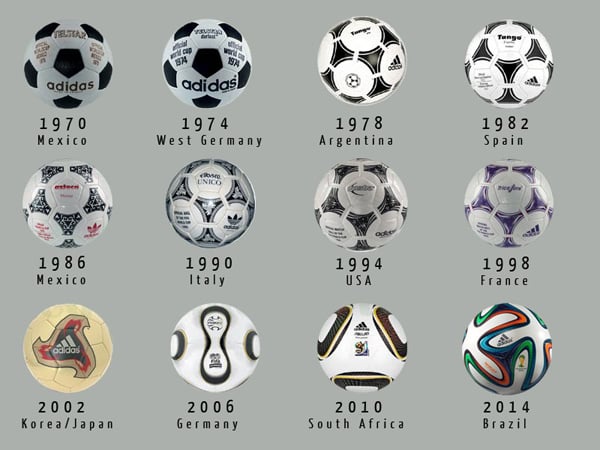

The real work began right then. It wasn’t just about listing the names; I had to figure out what actually changed year over year. I spent a whole afternoon comparing the 1970 Telstar to the 1974 Telstar Durlast. They looked identical—the iconic black and white 32-panel hexagon/pentagon design, made famous because it showed up well on black and white TVs back then. But the change was in the coating. The Durlast was supposedly waterproofed better. I had to verify this coating claim using old archived manufacturer press releases, not just fan wiki pages.

Then came the 80s. This is where things got interesting and required serious cross-referencing:

- 1982 (Tango España): They kept the same panel layout but started experimenting with rubber seams. This was a crucial step away from traditional stitching, trying to reduce water absorption even more. Still leather, mostly.

- 1986 (Azteca): This was the actual revolution. They ditched the leather entirely and used a synthetic material. Finally! No more bricks in the rain. I spent a good hour just appreciating this transition because this is the moment footballs became what they are today.

- 1990 (Etrusco Unico) & 1994 (Questra): More synthetic layers. The Questra had some fancy polyurethane foam layer, which I had to look up three times just to grasp what that meant for the average player. Basically, it made the ball bouncier and faster.

The Panel Count Chaos: 2002 to Today

The true technological chaos erupted in 2002 with the Fevernova. This is where the panel count started dropping. They went from the traditional 32 down to 20 highly complex triangles. This change made researching future balls incredibly difficult because every few years, the entire structure changed.

I had to create a separate spreadsheet just to track panel counts and bonding methods (stitched vs. thermally bonded):

- 2006 (Teamgeist): Down to 14 panels. Thermally bonded, meaning no stitching at all. This made the ball almost perfectly spherical.

- 2010 (Jabulani): Oh boy, the Jabulani. Only 8 panels. Steve hates this one. My research confirmed his bias: it was too round and too smooth, causing it to swerve wildly and unpredictably. Goalies hated it.

- 2014 (Brazuca): They fixed the Jabulani disaster by switching to a 6-panel design, which they roughed up a bit for better grip and stability.

- 2018 (Telstar 18) and 2022 (Al Rihla): They kept the same basic 6-panel structure but focused on material tweaks and making them even faster off the foot. The Al Rihla (2022) had a core designed for maximum acceleration, which meant I had to spend 45 minutes trying to understand foam density ratings.

The Final Outcome

After all that cross-referencing, verifying material shifts, and tracking panel geometry across 14 distinct balls, I had the whole log done. It wasn’t just a list; it was a clear path showing the transition from heavy, waterlogged leather to lightweight, thermally bonded aerodynamics.

I printed out the entire 15-page document, stapled it, and handed it straight to Steve. He read about the Telstar, the Azteca synthetic revolution, and the Jabulani panel reduction, his jaw practically hanging open. He tried to argue that the 1970 ball was still better, but I pointed directly at the entry for 1986 and reminded him that without the synthetic Azteca, his beloved old balls would still be unusable bricks in the rain. He finally conceded. I got my steak dinner, and more importantly, I finally understand the insane amount of technology that goes into something we all just call a “ball.” It was a huge, chaotic pain, but definitely worth the practice of digging this deep.