You know, for the longest time, I thought finding the correct Salah times was supposed to be easy. Just punch in ‘Nottingham’ on some random app, and you’re good to go. Turns out, I was spectacularly wrong. Dead wrong. It became this nagging thing, this tiny speck of annoyance that just kept growing until I decided, enough is enough, I’m solving this myself.

My family started complaining. Every other week, I was arguing with my wife about whether Maghrib was actually at 8:55 PM or 9:02 PM. Seven minutes doesn’t sound like much, but when you’re planning dinner, those minutes matter. I realized every single online source gave me a slightly different number. The mosque down the street had one calendar tacked up, the one I used online had another, and the app on my phone was just floating somewhere in the middle, making up its own rules, especially during the long summer days up here in the UK.

The Mess I Stepped Into: Initial Gathering

So, I decided to become a local authority on prayer times. This wasn’t about being pious; it was about getting rid of the constant low-level confusion. I grabbed a pen and paper—yeah, old school, don’t judge—and I started collecting data. I didn’t care about the source quality yet; I just wanted quantity. I started pulling information like a maniac.

- I downloaded four top-rated prayer time apps (you know the ones, everyone recommends them).

- I pulled the monthly PDF calendars from three different local Nottingham mosques.

- I cross-referenced these against two major international Islamic authority websites.

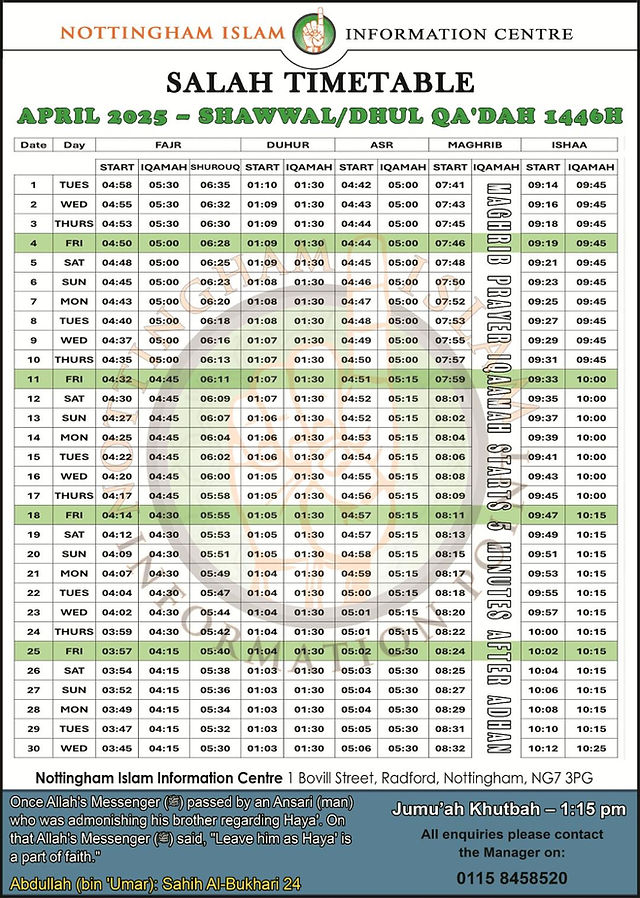

I focused specifically on the upcoming month, plotting Fajr, Dhuhr, Asr, Maghrib, and Isha. The results? A complete and utter statistical nightmare. The differences weren’t huge for Dhuhr and Asr, those were generally okay. But Fajr and Isha? They were all over the map. One source had Fajr at 3:45 AM, another insisted it was 4:10 AM. That 25-minute gap changes everything when you’re trying to sleep properly.

Digging Deep: Understanding the Calculation Conflict

I scratched my head, staring at the printouts. Why the massive difference? I thought they were all based on the sun’s position. They are, but it’s the methods they use for determining the twilight angle—especially for the extreme high latitude of Nottingham—that causes the friction. I wasn’t just comparing numbers; I was comparing methodologies. This is where I started pulling my hair out.

I realized I had to learn the names that mattered: Isna, MWL, UCL, and Shia Ithna Ashari. Each one uses a different angle of the sun below the horizon to mark the start of Fajr and the start of Isha. In the summer here, the sun barely dips below the horizon, which makes it impossible to use some of the standard methods without implementing what they call ‘high latitude adjustments.’

I spent an entire evening just reading these dry, technical explanations about astronomical twilight and nautical twilight. I felt like I was back in school, except this time I actually needed the information to function properly in life. I started comparing what calculation method each source was actually using.

Here’s what I found was the core issue:

Most of the local mosques, the ones known for accuracy, weren’t using the generic worldwide methods (like the Muslim World League). They were implementing a specialized “fixed angle” or “seven-night average” adjustment because during June, the true astronomical twilight never ends, meaning Isha would theoretically be at 1:30 AM and Fajr at 2:00 AM—which is useless for communal prayer.

The Practice: Choosing and Validating My Source

My goal shifted from finding all the answers to finding the one most accepted local answer that allowed for a sustainable schedule. I ditched the generic apps that clearly weren’t adjusting for high latitude correctly. They were useless to me in the summer.

I focused solely on the three local Nottingham mosques that I knew had established community committees. I discovered that two of them—thankfully—were synchronized. They both used the same modified method, likely implemented by a trusted regional body or council. This was my gold standard. It wasn’t the ‘perfect’ theoretical time, but it was the time the community actually prayed at.

My practice then became simple: I manually verified the calculation engine used by my chosen online source against the printed calendar from the most respected local mosque. I started with the next month’s data, cross-checking every single row. If my app said 4:10 AM and the mosque calendar said 4:10 AM, then that source earned a tick. If it varied by more than five minutes, I threw it out.

The process of comparison took three solid evenings. I was moving figures around in spreadsheets, highlighting the discrepancies in red, just to be sure. It was tedious, frankly, but the relief I felt when I finally nailed down a source that consistently matched the mosque was huge. It was like I had finally cracked the local code.

The Final Result: Sanity Restored

What I ended up with wasn’t a complex new calculation; it was simply a verified, reliable calendar based on local consensus, overriding the generic international databases. I finally created my own clean, printed monthly view, using only the data derived from the source that matched the reliable local mosque schedule. I printed it, laminated it—yes, I’m that guy now—and stuck it right on the fridge. No more arguments, no more guessing if I missed Jama’ah because the app was set to the wrong jurisdiction.

It taught me something important: Don’t trust global defaults when local realities are extreme. If you live somewhere far north like Nottingham, you have to throw out the standard rules and follow the established regional adjustments. I did the legwork so I don’t have to wonder anymore, and honestly, the peace of mind alone was worth the three nights of spreadsheet torture.