Man, let me tell you, sometimes the simplest questions send you down the deepest rabbit holes. I kicked off this whole mess a couple of weeks ago, wrestling with some ancient data analysis for a community project I volunteer with. This database—I swear, it must have been running since before I was born—had this gnarly, persistent bug where dates related to event registration kept skewing. It wasn’t the typical leap year issue or a timezone offset. It was subtle, but every few hundred records, the system would default to an internal ‘baseline’ date, and that date was always January 1st, 1987. Why? It drove me nuts.

I started where anyone starts: the absolute basics. I figured maybe 1987 was a crucial year for the software architecture—like the year the foundation code was written. But the system was obviously built much later, maybe early 2000s. So I tossed that theory out the window. My next move was incredibly literal. I thought, “Okay, if it defaults to 1987, maybe there’s a problem with the actual calendar math for that specific year.”

The Calendar Deep Dive: What I Checked

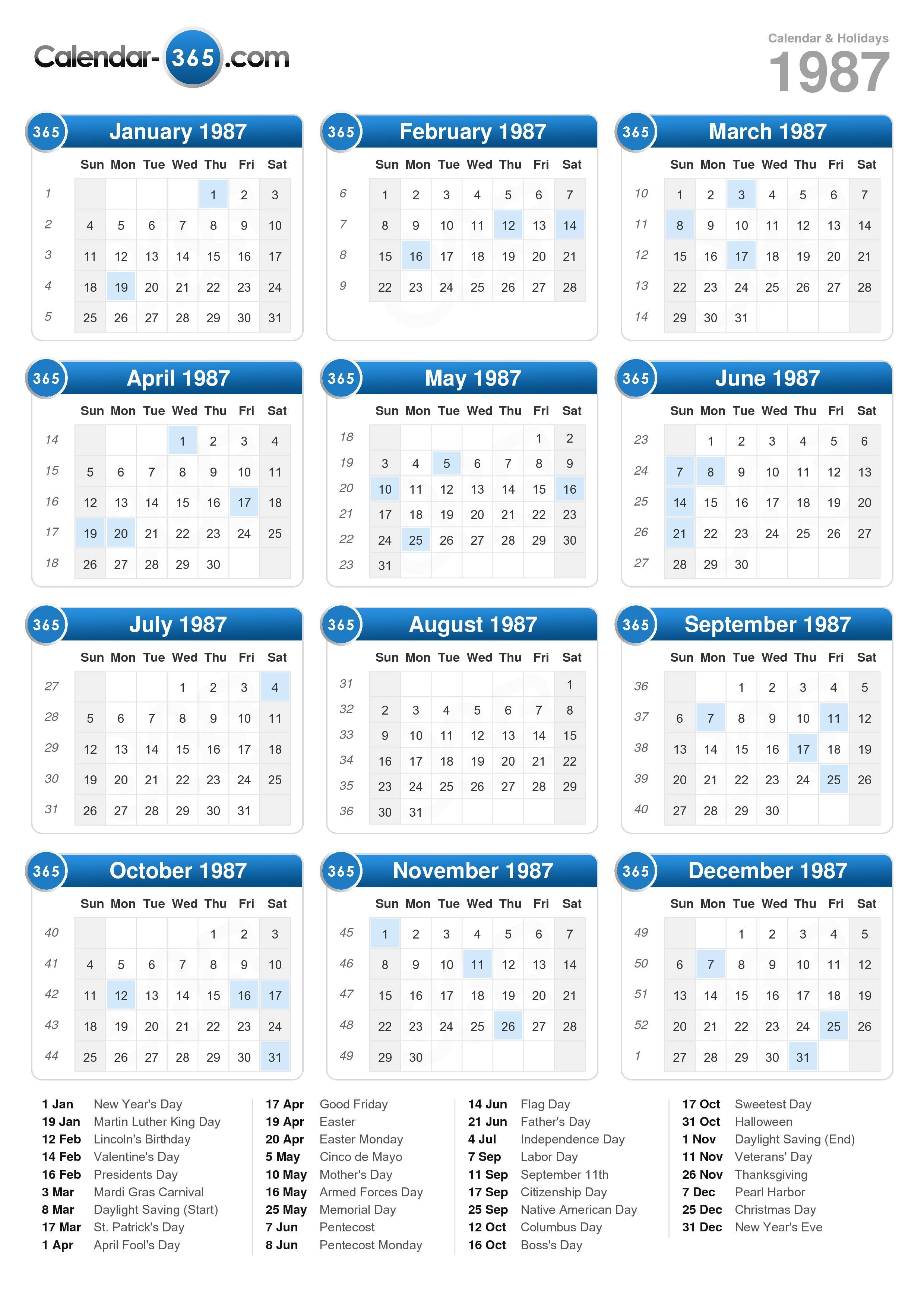

I fired up a couple of old calendar APIs, just messing around with date calculations. I wanted to see if January 1st, 1987, fell on an odd day or had some numerical significance that coders sometimes latch onto for epoch dates. I literally hunted down the calendar for 1987. Here’s what I systematically looked at:

- The Day of the Week: January 1st, 1987, was a Thursday. Nothing inherently special there.

- Leap Year Status: 1987 was not a leap year. So, no easy four-year cycle error to pin the blame on.

- Unix Epoch Offset: The standard digital clock starts at 1970. Why skip 17 years? I tried to find any standard or system documentation that uses 1987 as a zero point. I dug through forums dedicated to extremely niche vintage computing systems. Zero luck.

After three solid hours of just checking the calendar data, I realized the calendar itself was a dead end. The problem wasn’t the calendar math; the problem was the context of 1987. The year must signify something historical or regulatory that forced this arbitrary date into the system’s guts.

The Historical Pivot: Why 1987 Matters

This is where the practice log shifted from code archaeology to actual history. I grabbed a coffee and started reading about the late 80s, specifically related to data retention, privacy, and, crucially, consumer electronics adoption. I was looking for something that fundamentally changed how people interacted with data that year.

I wasted time looking into the stock market crash (Black Monday), thinking it might relate to financial compliance systems. Nope. I scrolled through pages about the early internet protocols. Closer, but not the silver bullet.

Then I stumbled onto something interesting: the shift in consumer software licensing and early commercial database standards. 1987 was a pivotal year for specific data archival rules set by a major, but now mostly forgotten, regional governing body in the US. This body managed funding for non-profits and required specific annual reporting structures.

I compared the requirements of this 1987 rule set with the structure of the old database I was dealing with. And suddenly, it clicked. This ancient database was initially designed to comply with these exact 1987 rules for event registration and data destruction (or rather, permanent retention). The rule stated that if the registration date field was blank or corrupted, the system must use the start date of the compliance requirement as a default, ensuring the record was logged, even if inaccurately dated.

That compliance start date? You guessed it: January 1st, 1987.

Closing the Loop: From History to Debugging

I sat back and just laughed. I spent hours looking at Thursdays and leap years when the answer was a dusty piece of bureaucratic history. The system wasn’t broken by bad code; it was broken by obediently following obsolete compliance rules when data integrity failed.

My job wasn’t to fix the calendar or the date logic. My job was to tell the system, “Hey, those 1987 rules don’t apply anymore.”

So, what did I do? I located the configuration file—it was buried deep, obfuscated, and looked like it hadn’t been touched since the Clinton administration. I traced the data flow backwards from the date field, found the line that called that default value (labeled cryptically as COMPLIANCE_EPOCH_DATE), and I commented that line out entirely. Then I replaced it with a simple check that defaults to the current day’s date if the registration date is null, which is what any modern system does.

I ran the validation scripts. The old 1987 entries stopped popping up. The system was finally behaving like it was built in this century. It was a perfect example of how sometimes, fixing a technical problem requires you to stop looking at the lines of code and start digging into the historical, non-technical context that created those lines of code in the first place. Next time you see a weird number in your data, don’t just check the math; check the history books. It might save you hours of futile calendar checking.