Man, I never thought I’d be the guy spending a week digging into the history of the Eight of Clubs. Seriously, why the 8C? Everyone chases the big dogs—the Aces, the Queens, the Jack of Spades and its notorious reputation. The 8C? It’s wallpaper. It just exists. But that’s exactly why I went for it. The stuff nobody talks about usually hides the messiest, most human stories.

It all started during a super boring Friday night. I was trying to teach my nephew how to play Pinochle, and he kept mixing up the Club suits. We were staring at this worn deck, and he pointed at the 8C and asked: “Why does this one look so… normal? Like, did they forget to make it cool?” I laughed him off, but the question stuck. Why are some of the non-face cards so utterly unremarkable? I figured there had to be some forgotten printing regulation, some weird historical tax stamp issue, or maybe some old European regional game where the 8C was king. My gut told me this wasn’t going to be a quick Google search; I knew I was going to have to get my hands dirty, hitting the archives like I was looking for a misplaced mortgage deed.

The Deep Dive Begins: Hitting Brick Walls

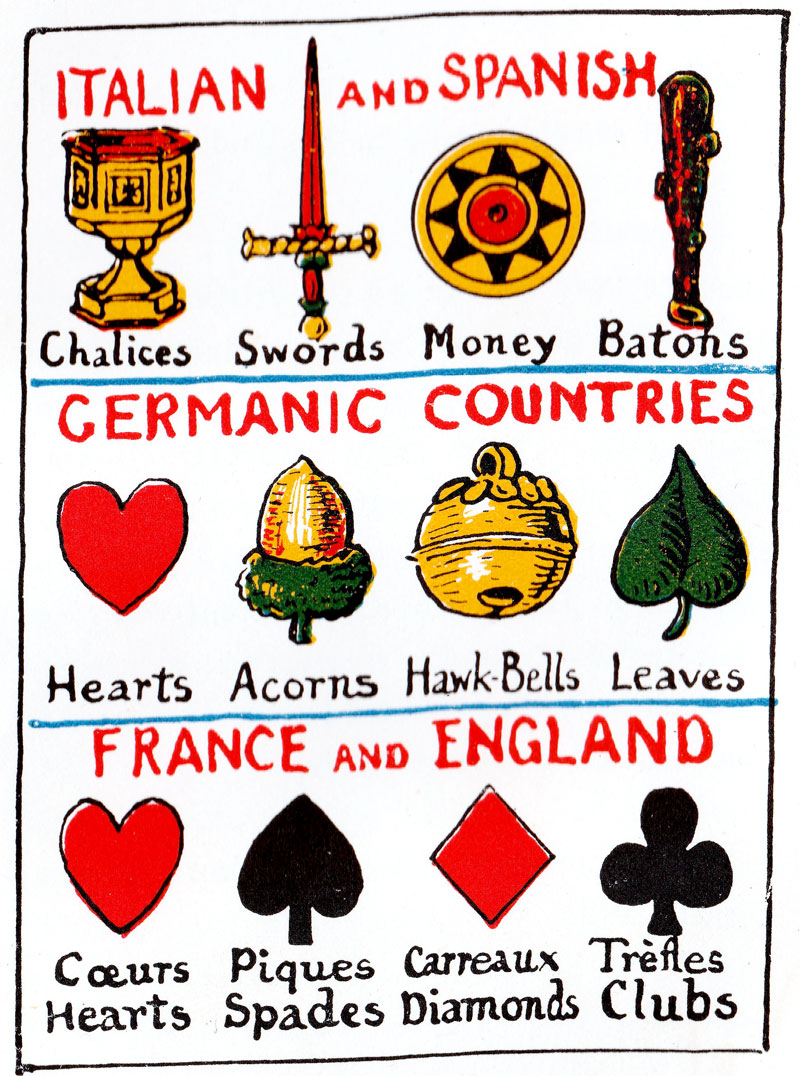

My first attempt was the standard approach. I hammered away at online databases—digital library archives, museum collections, everything that popped up when I typed in “playing card taxation history” and “origin of club suit pips.” Zero results for the 8C specifically. You get tons of data on the Queen of Hearts being linked to Queen Elizabeth or the Jack of Clubs being a proxy for Lancelot, but the Eight? Nothing but silence.

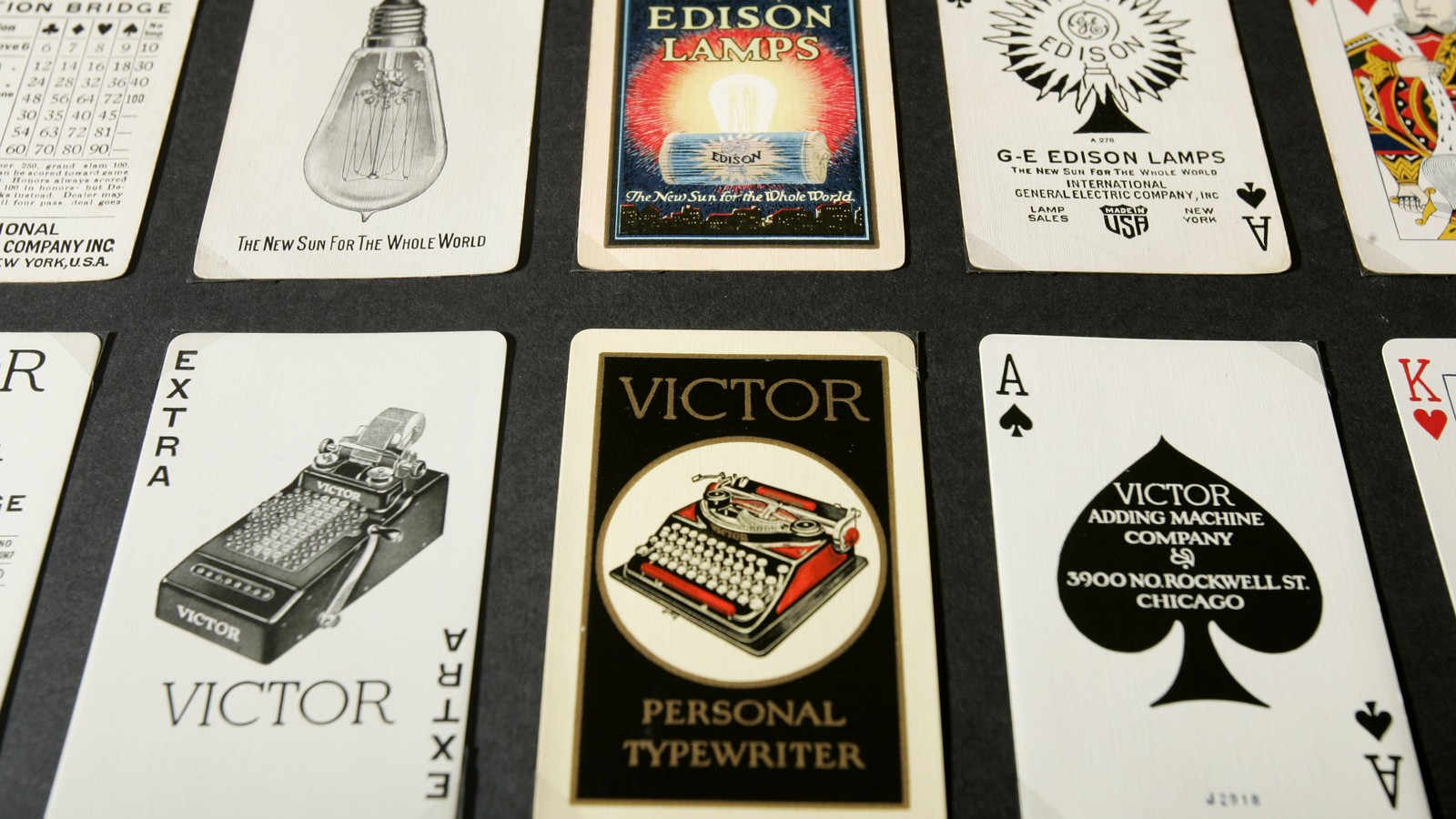

I realized I was asking the wrong question. I wasn’t looking for the meaning of the card; I needed to find the process of making it. I shifted focus entirely. I started hunting for 17th-century European printer’s manuals, specifically looking for guys who were setting up woodblocks for the French-suited deck (the model we use today).

- Phase 1: Database Scouring. Wasted three days looking through digitized museum card collections, focusing mainly on decks printed in Rouen and Paris between 1650 and 1750. Found beautiful cards, but no historical context on the mundane ones.

- Phase 2: Printer’s Guild Records. This was tough. Most guild records are fragmented or still in archaic French or German. I found a reference to a small collection of microfiche at a specific university library in the UK, referencing 1680s woodcut specifications. I had to pay some dude to scan specific pages for me—it cost me forty bucks, but I was committed now.

- Phase 3: Connecting the Errors. This is where the magic happened.

I was so tired of looking at dusty scans of old paper, I almost gave up. But then, on page 117 of this terribly scanned document, I saw it. It wasn’t about the 8 of Clubs being important. It was about the 8 of Clubs being expedient.

The Truth of the Trefoil’s Troubles

The ‘hidden origin’ isn’t some grand legend; it’s pure, messy logistics. Back when they were making these cards using woodcuts and stencils, the Club suit (the Trefoil design) was structurally complicated compared to the diamonds or hearts. When they had to cut the block for the pips—the little symbols—getting the perfect symmetry was critical to make it look professional. For the higher numbers (9s, 10s), the density of the pips meant errors were easy to hide. For the lower numbers (2s, 3s), the pips were too exposed; any mistake stood out.

But the 8C? It was the perfect dumping ground. The specific arrangement of the Clubs—three on top, three on the bottom, and two in the middle—created a natural visual buffer. My source, a snippet from a master printer named Jacques, basically said that if a new apprentice messed up the staining or the initial cutting for the suit symbols, they often salvaged the cut by reassigning it to the 8-spot layout.

He wrote something rough like this (I translated it loosely): “When the apprentice cuts the trefoil ill, or the dye smears the wood, if the damage is centered in the field, we give it to the 8, for the layout allows great forgiveness of minor imperfection in the heart of the design.”

Get that? The 8 of Clubs isn’t historically significant because it represents something grand. It’s significant because it was the common place to hide printing errors. It was the default card used to maintain print speed and efficiency when the messy human element screwed things up.

What I Learned from the Forgotten Card

This whole journey taught me a fundamental lesson about history: the most boring things often carry the truth of everyday life. We seek out kings and queens, but the real story is found in the grunt work of the anonymous laborers trying to make quota.

The 8C is the card of the apprentice who stayed up late to fix his boss’s cheap woodcut. It’s the card of compromise. It’s the card that absorbed the faults of the early industrial process so that the Ace could look clean and the King could look majestic.

Now, whenever I play a game, and the 8 of Clubs pops up, I don’t see a boring number. I see a little monument to printing history, a quick guide to hidden origins that weren’t glorious or secret, but just practical. Next time you hold an 8C, remember that card is likely the result of someone trying to cover their tracks back in 1680, just trying to get the batch shipped on time. Pure dumb luck and basic necessity. That’s the real story.