Man, let me tell you, this week was supposed to be about fixing the leaky faucet in the downstairs bath, right? But you know how these things go. I pulled out one storage bin from the back of the garage, the one my wife kept saying was full of “sentimental junk,” and bam. There it was. My Grandpa Leo’s old hat box. That thing must have been sitting there since the 80s, smelling faintly of mothballs and old leather.

I opened it up and there was this beautiful, slightly crushed, old fedora. Not fancy, just sturdy. Now, Grandpa Leo was a character, always wearing a hat. Rain, shine, indoors sometimes—he had that thing glued to his head. I just stood there thinking, why? Why did everyone back then just wear a hat, all the time? It felt like a small, stupid question, but once I started digging, things got messy fast.

The Initial Dive and Getting Drowned

I didn’t start with “European hats,” no way. I just typed in: “Why did men wear hats 1950s.” Instant overload. Pages and pages of fashion blogs, etiquette guides, and people arguing about Frank Sinatra. I scrolled and scrolled, and realized I was looking at the end of the story, not the beginning. The 1950s were when the hat died, not when it was born.

I had to reset. If I wanted to know why the fedora existed, I needed to know what came before. So I pivoted hard and punched in: “History of headwear status Europe.” That’s when the real history started kicking in. I mean, hats weren’t just for keeping the sun off; they were basically ID cards, telling everyone exactly where you stood on the social ladder.

Status Symbols: When the Government Regulated Your Head

The first thing that shocked me was just how regulated headwear used to be. I spent about three hours just pouring over Tudor-era stuff, mostly looking at England and France. Seriously, in 1571, England actually passed a law about hats! Imagine the government telling you what kind of cap you had to wear. It wasn’t about fashion; it was about boosting the wool trade. But here’s the kicker—it only applied to working people. The rich folks? They could wear whatever expensive silk monstrosity they wanted. This immediately showed me the core idea: Headwear equaled social standing.

I made a quick list in my notes to keep track of the cultural weight:

- The Medieval Coif: Simple linen cap, practical, kept the hair clean, often worn under other hats or armor. It established the base layer of modesty and practicality.

- The Tudor Flat Cap: This became mandatory for commoners on Sundays and holidays because of that 1571 statute. If you were wealthy or noble, you were specifically exempted. If you were caught without it, you got fined. A working man wearing an expensive velvet bonnet instead of the regulated wool cap was basically trying to look like someone he wasn’t.

- The Chaperon/Bourrelet (15th Century): This one was wild. It started as a simple hood, but the wealthy manipulated the fabric until it became a huge, padded donut resting on the head, often with a long fabric tail draped down. It was huge, impractical, and expensive, which made it perfect for showing off.

Every change in design I traced back always came down to two things: showing off wealth, or adhering to military practicality. Nothing was accidental.

The Revolutionary Shift: From Feathers to Felt

I jumped forward a few centuries because things got too frilly with the powdered wigs and the tiny hats on top of them in the 17th century. The wigs were the status symbol then, and the hat just became something to be held or tucked under the arm.

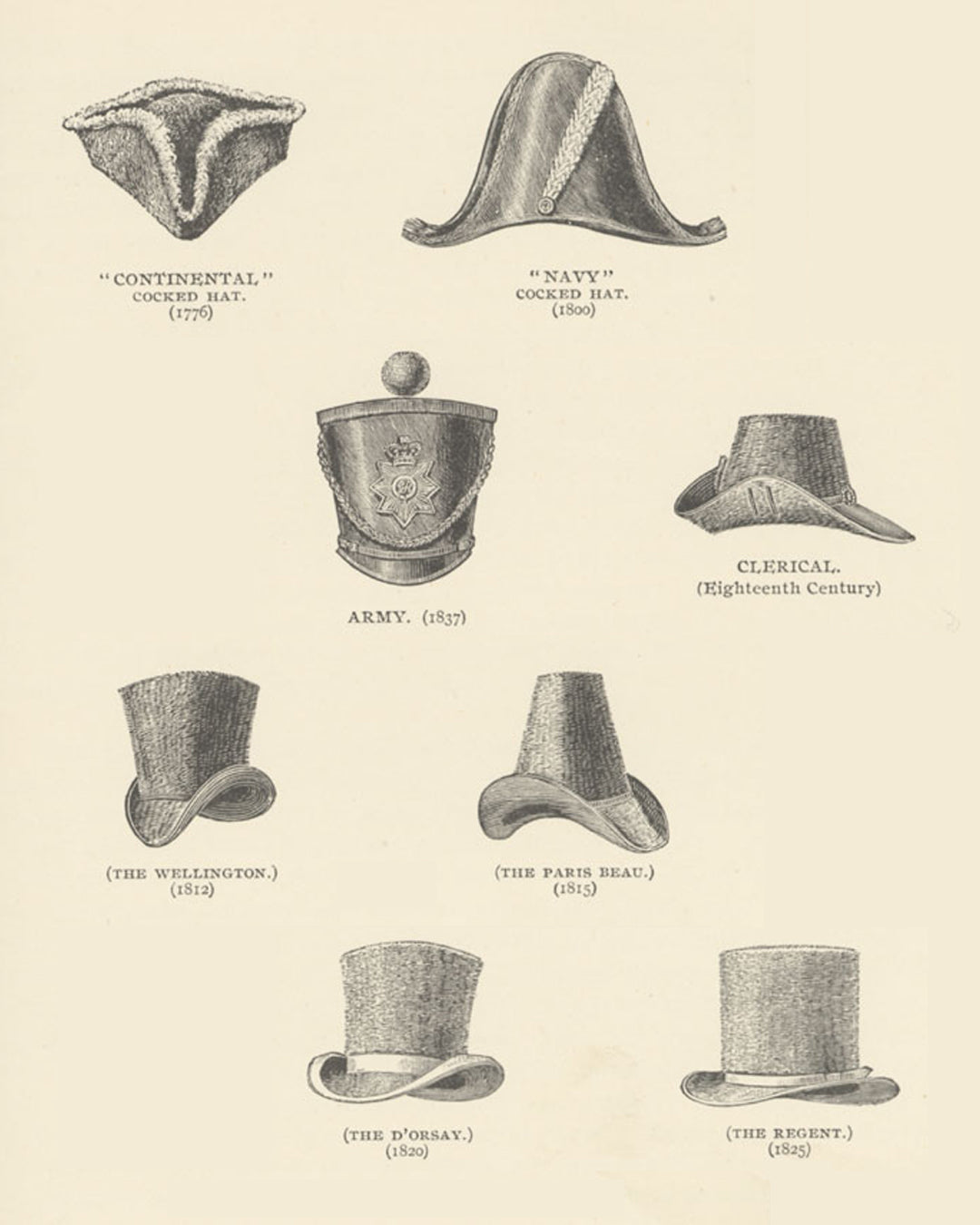

The 18th century gave us the Tricorn, which was popular with the military. I realized why: folding the brim up in three places made it practical for soldiers because the wide edges kept the rain off but didn’t block the view when they were carrying a musket on their shoulder. Utility briefly won over pure status.

But the real game changer, the thing that lasted and defined respectability for over a hundred years, was the Top Hat. I looked up the famous story about the guy who first wore one in London in 1797. Apparently, when John Hetherington first stepped out wearing this tall, black, shiny tube on his head, people lost their minds! Women fainted, kids screamed, and he was actually arrested for disturbing the peace! It was so new and shocking because it was so drastically different from the shallow, colorful hats that had come before.

Why did it stick? Because it was industrial. It was tall, serious, and matched the rising seriousness of the Victorian businessman. It wasn’t flowery or aristocratic; it was powerful and simple. It established the rule: If you were serious about business, you wore the Top Hat. It was basically a uniform that screamed, “I have money and I am respectable.”

Bringing It Back to Grandpa Leo

So, I went back to the garage, holding Grandpa Leo’s fedora again. It’s funny how all that history—the status laws, the industrial shift, the need for respectability—all filters down to this one piece of felt. The fedora itself was born out of the need for something softer and more manageable than the stiff bowler or the super-tall top hat, reflecting a slightly more casual (but still respectable) 20th century.

My final takeaway after hours of digging is that the European hat was the ultimate visual barrier—it defined who was allowed in which social circle. Its decline in the mid-20th century really mirrors the decline of rigid social classes and the rise of casual culture.

It’s a massive topic, and I only scratched the surface of the political, religious, and military influences. But the core lesson I pulled out? A hat was never just a hat. It was always a loud, visible sign of who you were, where you stood, and whether the government thought you were worth regulating. Next week, I might actually fix that leaky faucet. Or maybe I’ll start charting the history of the European boot. We’ll see!